Farm Fresh Local Food for All

6 min read / July 26, 2023 / By Rachel Mullis

Our website uses cookies to improve your experience. To learn more about how we use cookies, please review our privacy policy.

Can't find what you're looking for? Please contact us.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Christine Borque found herself busier than ever, cultivating vegetables for the community. “I didn’t experience lockdown as being in your house because I was outside, growing food,” she said. They scaled up from 50 to 85 CSA shares overnight.

Christine runs Blue Heron Farm in Grand Isle together with her partner, Adam, and their daughters. They’ve offered a sliding-scale CSA since 2004. But in 2020, they reframed it as a pay-what-you-can CSA for their community—even if some couldn’t afford to pay anything. It began attracting the attention of those who could pay a little extra.

“I was at the farmstand, watering,” Christine recalled, “and a guy said, ‘Hey, I heard you’re doing these pay-what-you-can shares. Here’s a hundred dollars. Thanks for doing that for people.’”

The gesture is one example of the spirit that’s connecting farmers with their communities.

Blue Heron Farm in Grand Isle is run by Christine Bourque (third from left) with her partner, Adam (far right), and their daughters Delia and Sadie (from left). They offer subsidized CSA shares and work with a host of community organizations to ensure affordable local food for all. Photo by Caleb Kenna.

The pandemic revealed the massive scale of Vermont’s hunger crisis, while emergency government funds opened new avenues for farmers to meet the need.

“There has been an incredible increase in people accessing food through the charitable food system,” said Michelle Wallace, Director of Community Health Programs of the Vermont Foodbank, which distributes food statewide. “And that hasn’t decreased all that much since the height of the pandemic.”

The Foodbank’s Vermonters Feeding Vermonters program began in 2018 with $60,000 in direct food purchases from Vermont producers. In 2022, the budget increased to $2.4 million.

Some pandemic-era efforts are winding down but several VLT-conserved farms like Christine’s continue to work with the Foodbank, food shelves, gleaning organizations, farm-to-school, and health programs—to make their products available to more people.

For example, Christine has worked with the Grand Isle food shelf, NOFA’s Senior Farm Share program, and Food for Thought in South Hero—a program providing meals to 140+ kids in summer.

Blue Heron Farm now accepts electronic payments through the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and offers subsidized CSA shares, funded by community members and by NOFA Vermont through its Farm Share Program.

Christine and Adam have master’s degrees in social work and community mental health, which has proven useful in finding ways to meet more peoples’ needs.

A volunteer packs fresh zucchini and cucumbers into bags for distribution to neighbors across the state at the Vermont Foodbank facility in Barre. Credit: Vermont Foodbank

Farmers are also working with nonprofits to expand what is offered through the charitable food system to include foods that are culturally meaningful.

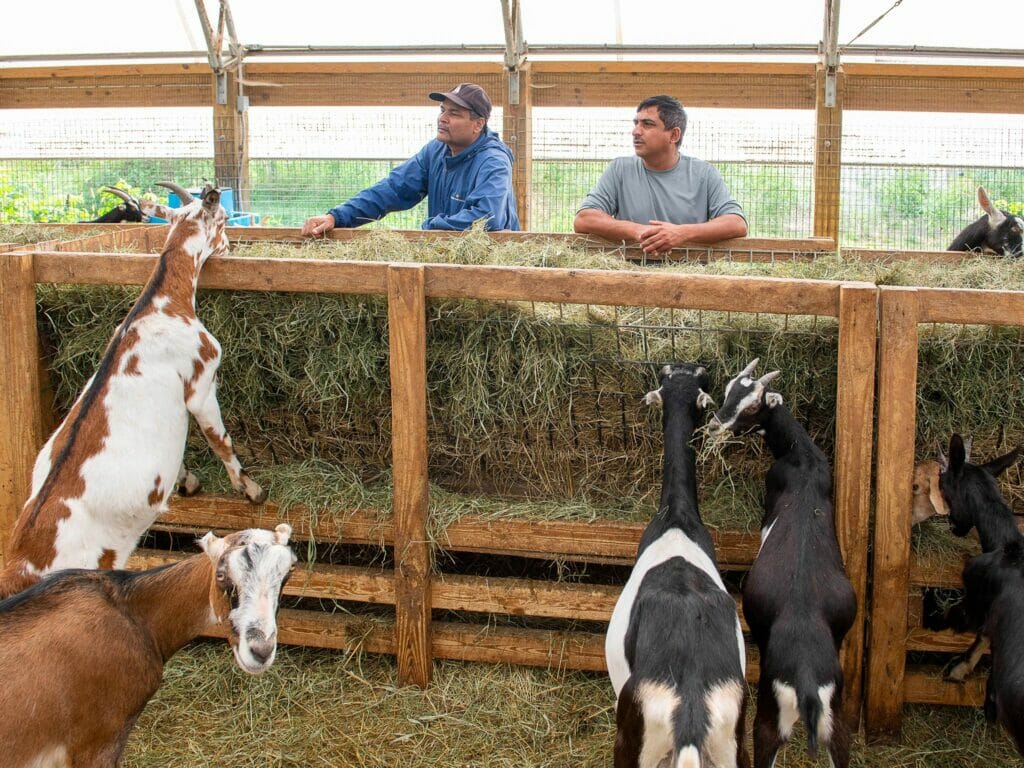

One of those farmers is Chuda Dhaurali, who recently bought VLT’s Pine Island Community Farm in Colchester after running a goat farm there for years. The farm is now called Dhaurali Goats, and some of its customers—many of whom are first-generation Americans like Chuda—can buy goats with a Foodbank voucher.

Originally from Bhutan, Chuda and his wife, Gita, started the farm in 2013, when no fresh goat meat was available in Vermont. Today their 500-goat farm serves families with roots in Africa and South Asia for whom goat meat is a staple and selecting a live goat is important.

“Some families can buy the meat they need for a month, with the voucher. So it is very helpful for them and they are happy,” said Chuda. “It helps the community, and it helps the business also.”

Chuda Dhaurali (right) participates in a Vermont Foodbank program. He’s pictured here in his goat barn. Photo by Caleb Kenna.

Another hard-to-find food in Vermont is African eggplant. That is, until Janine Ndagijimana of Janine Farm began leasing eight acres on another VLT-conserved farm in Colchester. This season, she’ll grow over 22,000 eggplants, plus amaranth and African corn. Some will go directly to the Foodbank for distribution.

Born in Rwanda to Burundian refugees, Janine helped her parents grow food. Later, while in a refugee camp in Tanzania, she began to buy and sell vegetables, honing her business skills.

“I love it,” she said. “It’s the same job my parents did. It’s a good thing to do.”

Nearby, at the VLT-managed Pine Island Community Gardens, more than 70 families from 10 countries grow amaranth, hot peppers, bitter melon, greens, and more—foods not usually found on a Vermont farm.

Thousands of African eggplants are grown at Janine Farm in Colchester. Photo by Kyle Gray.

Further south, in West Haven, another conserved farm is easing the sting of food prices. “The need is enormous and fresh produce is expensive,” said farmer Tanya Tolchin of Otter Point Farm. “I have to buy it in the winter, so I know.”

Otter Point is a supplier for the Farmacy Project of the Vermont Farmers Food Center in Rutland County. The project serves about 250 people and provides free or deeply discounted produce to those with a doctor’s prescription for more fresh fruits and vegetables.

“When we started our farm in 2018,” Tanya said, “we were focused on the next generation of local food, [things like] farm-to-school and institutions like hospitals—all the other places where local food should be.”

For Tanya, working with local partners is a win-win that establishes a reliable market and reduces distribution costs. “We really like selling wholesale [to the Farmacy] and moving the product as quickly as we can, [compared to] farmers’ markets or some of the other ways of selling produce, which can be much more time consuming.”

Looking forward, all four farmers plan to continue to grow and produce food that goes beyond standard market outlets.

“Farming is being able to help feed people and make it accessible,” said Christine. “It just seems like a no-brainer to us to do this.”

We generally send two emails per month. You can unsubscribe at any time.